The Ins and Outs of Weeding

I am actually shocked it has taken me this long to write this post about weeding. Weeding is one of my absolute favourite collection management tasks.

Weeding is also known as deaccessioning, culling or deselection. It’s the process of carefully removing items from your school library collections using a specific criteria that meets your collection development policy.

I know weeding – choosing to remove an item from your collection – can be overwhelming for some library staff. But, regardless of if you are a weeding lover or hater, it must be done. Let me repeat that for those in the back. We. Must. Weed. Our. Collections. It is a vital and very important library task.

Why weeding?

Culling items from our collection ensures that our collections remain relevant and useful to staff and students. It keeps our collections in top physical condition. It ensures there is room on the shelf for new titles. It means students and staff are more likely to find the resources they need and are not overwhelmed trying to find the relevant titles in the midst of titles no longer useful to them.

Weeding criteria

When weeding, you use criteria to help you make decisions about what items to keep and discard.

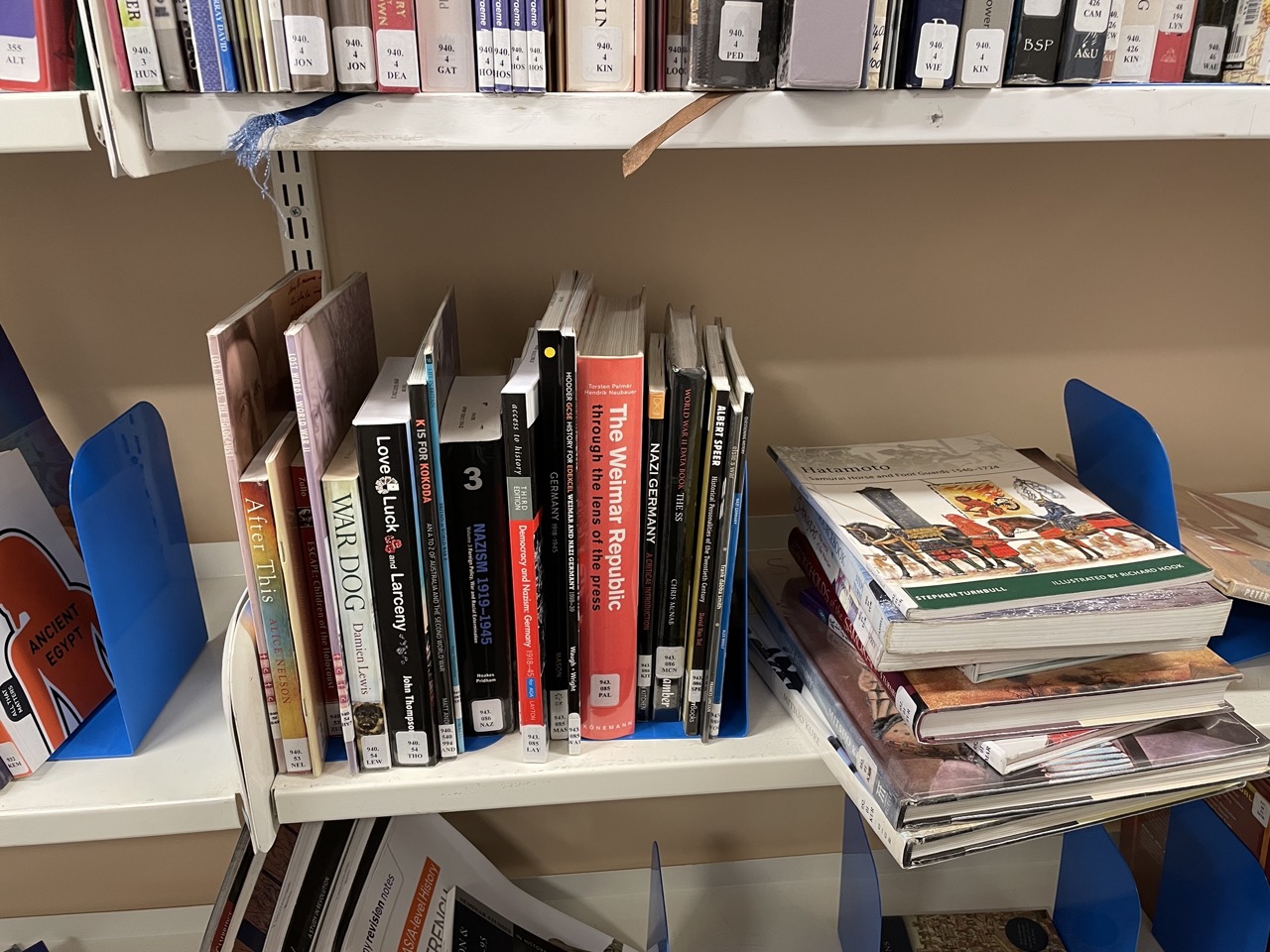

Condition

Weeding for condition might be the easiest type of weeding. It’s something you can see and helps to keep our collections in great condition. You should remove a book that is mouldy, moisture-damaged, yellowing, damaged, beyond repair or outdated. Remember, your collection should be safe for everyone to touch. Just because you are not allergic to mould and dust doesn’t mean your students are immune to these dangers. Removing mouldy and moisture-damaged books can prevent this spreading to the rest of your collection. Book mould happens, particularly in humid parts of the world. Having spaces with more ventilation, books not jammed onto shelves, and air conditioning can all help. If you have books with mould or moisture damage that you have to keep, remove them from the majority of the collection and keep them in sealed containers.

Removing aged books or books with dated formats and covers is important for circulation. Students don’t want to use something that isn’t relevant to them and an outdated cover that screams the ‘80s (or ‘50s) let’s them know the information inside probably ins’t going to be of use to them. It’s the same with layouts and photographs used in the books.

If the information within is good but the condition is bad, keeping it depends on your usage needs. If a teacher can use it as a reference source, keep it separate from the rest of the collection. Can you source a new replacement copy? If not, assess if a student is likely to pick up the book due to its condition, regardless of the usefulness of the information within. It might be a fantastic story but if the book is disgusting, no student is going to take that home to read and it’s just taking up valuable shelf space.

Age

Yep, old books need to go. Sometimes. For some books, age isn’t relevant – our classic titles are still in use but I have purchased new copies. Other times, age is a deciding factor. A book on web design from the early 2000s is going to be completely out of date. You’ll find guides from other librarians about set dates to consider for your weeding, 5 years old for technology section, etc. I don’t stick to set dates, instead judging each book individually, the information contained, the context and the need. Some books are old but primary sources and need to be kept for those reasons.

Format

Sometimes, formats become obsolete and can be discarded. VHS tapes, even DVDs now have been replaced by online video databases.

Usage

Use your library management system to create a report of items that have not circulated in a set number of years, 5 years is a good starting point. Assess why the book might not have been used. Perhaps it’s a condition issue, perhaps it’s the second book in the series and the first book has been missing for 5 years. Sometimes, non-fiction titles get used within the library space and not loaned, so circulation stats cannot be used alone to decide on an item’s fate. Use your judgement – does it still get used in the library, would an updated copy help? Or is it no longer needed and can be discarded.

Accuracy

While age can help you check for accuracy of information, particularly for non-fiction resources, you might still need to check newer resources. Containing accurate information is key to a resource’s usefulness. If information is no longer correct, the resource needs to be culled.

Relevance

Is the item useful to your staff and students? The information or text might be accurate, but if it’s not relevant, not something they need to access, no longer of interest, or not something they study, then assess if you need to keep the resource. Sometimes, texts must be kept for a few years because the curriculum cycles through topics. Other times, if it’s no longer relevant, that biography personality isn’t someone the students relate to, the story no longer something students connect with, then it can go.

Cultural Appropriateness

The resources in your collection need to meet current cultural standards and practices. How resources once spoke about certain groups is changing (thank goodness!!). We are far more aware of the way information should be shared about cultures, groups and populations. Our collections need to reflect this. Check for standards that your resources should be using, check resources for racism, sexism, ageism, or are positioned from a historically powerful voice that marginalises the voices that should be discussing a topic.

Here’s an example, when assessing books about Australian First Nations peoples, check who is the book written by, if it acknowledges where the information was gathered from, follows appropriate First Nations cultural practices (like an acknowledgement of which lands the book was written upon, acknowledging elders of the community, warning of use of names of those who are deceased), and uses present tense when talking about First Nations peoples (unless taking about a specific historical event).

Aligning to your collection development

When using any or all of the above criteria, consider your collection development policy. Many of the above criteria should be in your policy, but you might have additional criteria, a weeding policy that sets how frequently you weed each collection or what to do with weeded books.

Where to start

Pick your criteria

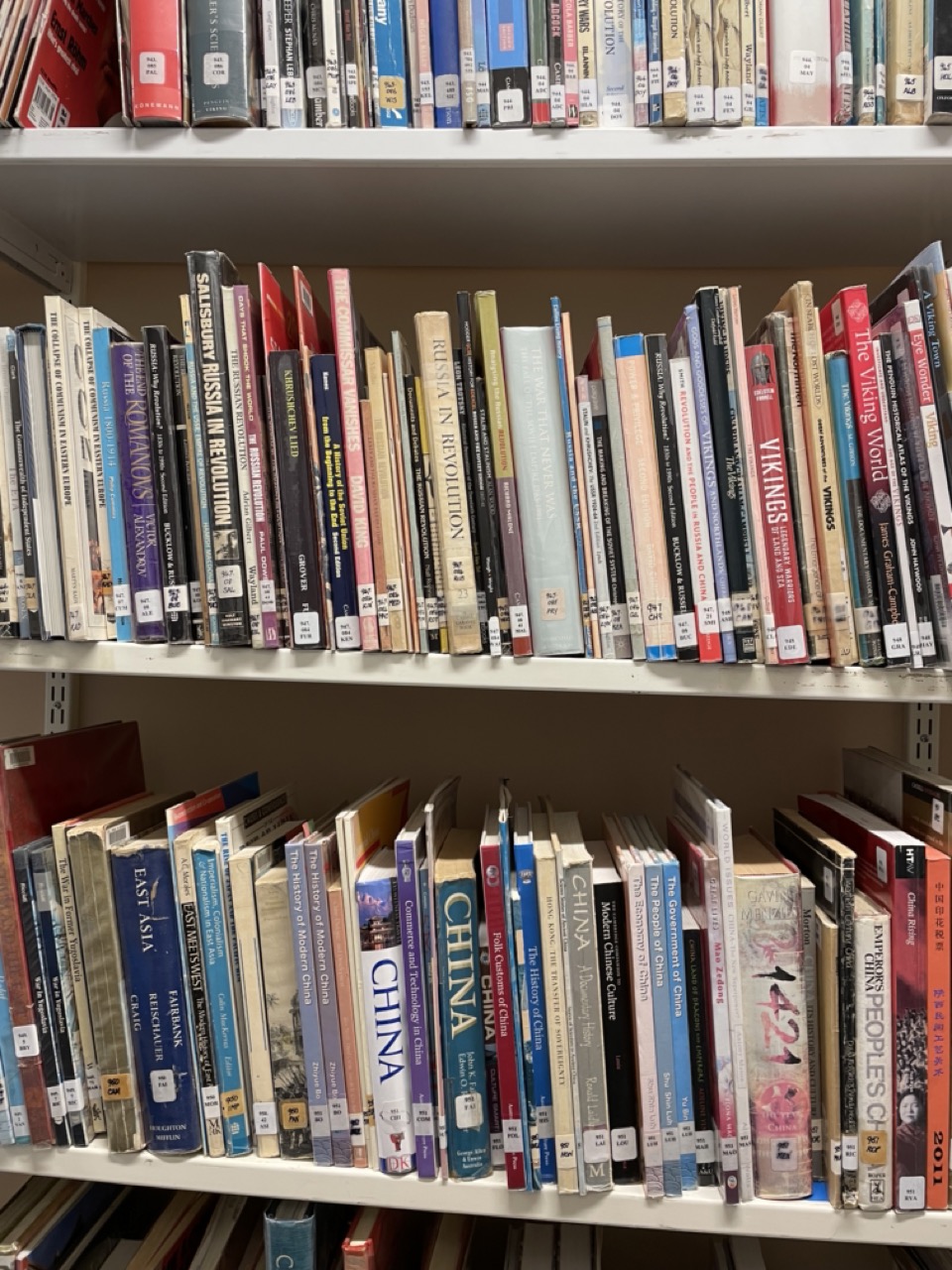

When weeding, which criteria you start with depends on the collection you are working with. With the non-fiction collection I inherited at my current school, I started with (and basically only used) condition, age and format. The books were so old, so mouldy, and so damaged that I disposed of 90% of them using condition alone. The VHSs and DVDs were quick to follow. Now, with my newly reinvigorated non-fiction collection, I’ll be weeding on relevance, accuracy and usage.

For some collections or sections, a certain criteria is going to be more important, like accuracy for a technology section, or usage for a fiction collection. Select the criteria that best suits. Ensure that it aligns to your collection development policy.

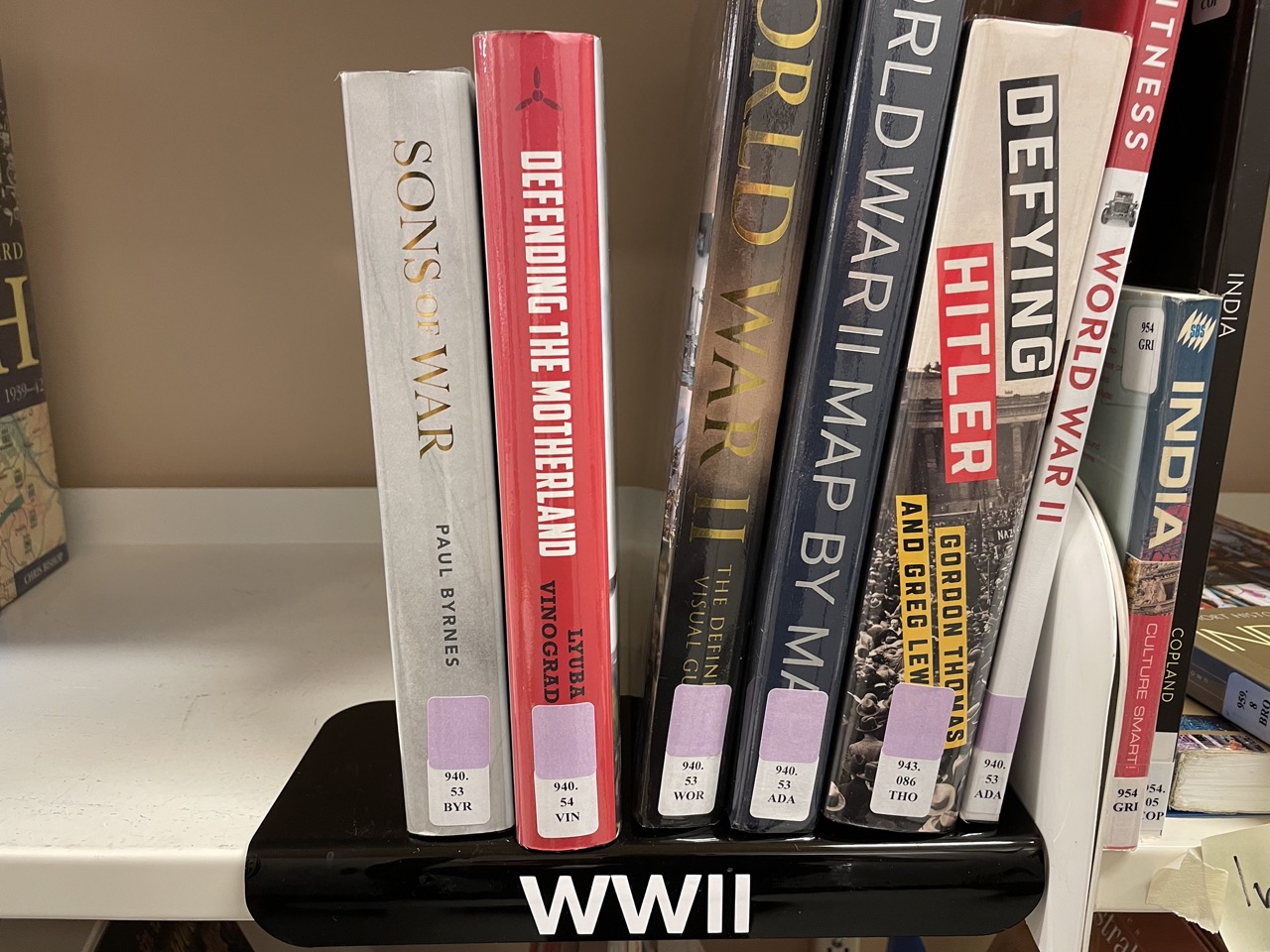

How to weed

Once you’ve selected your collection and criteria, dive straight in. Having a trolley with you to place your discarded books on helps. If usage is a criteria you are using, you’ll need a printout or computer displaying your usage report from your library management. Pull the books you choose to cull from your collection. You then might do follow-up checks on some of them. I often create an “I’m not sure” pile of books I think I might weed, but want to double-check. Books you choose to discard need to be removed from your library management system. Follow your system’s instructions on how to do that. You then need to cover, blackout or remove the barcodes.

Discarding weeded books

You have a few options for discarding weeded books and each depend on what criteria you used. If you’ve culled for condition, accuracy, or cultural appropriateness, then the bin is the best place for them. Please do not send these books to other countries, schools or charity shops. If you remove the covers, the insides can be recycled.

If you have culled using relevance or usage, then these books can be boxed up and delivered to a local charity shop or sent oversees to countries who need extra resources.

But I’m not sure…

If you end up with a “I’m not sure” pile you just can’t bring yourself to remove, then box them up, label them and change the location or status in the catalogue. Store them for a few months or even a year if you are really unsure. If you don’t have to go diving into that box in that time, it’s safe to remove them from the system and get rid of them.

The end result

Weeding gives you much needed space on the shelf. It makes it easier to genrefy a collection, provides space for dynamic shelving or forward facing titles. It makes it easier for students to find the titles relevant to them. Yes, using the above criteria sometimes means you have to be harsh. Fewer books is better than the wrong books taking space on your shelves.

This is a great article, thank you! Any suggestions what do do with old non-fiction books pre-2000s. I don’t think donating these books to any ‘lifeline’ shop or second hand book shop would be worthwhile, but interested to hear your viewpoint?

Thank you!

Michelle

Thank you. I totally agree. It does depend on the book’s content and condition. If the book’s content is significantly outdated, irrelevant, or misleading I believe we should not be donating them, to overseas communities or our local shops. Same for books in poor condition. I think the best option is to recycle them. Take the covers off and the pages can go in the recycling bin. The books I’ve weeded recently were in such poor condition and so old, I didn’t donate anything, they all got binned.