Driving Innovation

Innovation, innovation, innovation. Have you seen the movie The Hundred Foot Journey? Great movie. In it, a young and upcoming chef moves to the city to work at a top restaurant. On his first day he is told “This is the beast with a thousand mouths, that must be fed twice a day. And what does the beast like? Innovation. Innovation. Innovation.”

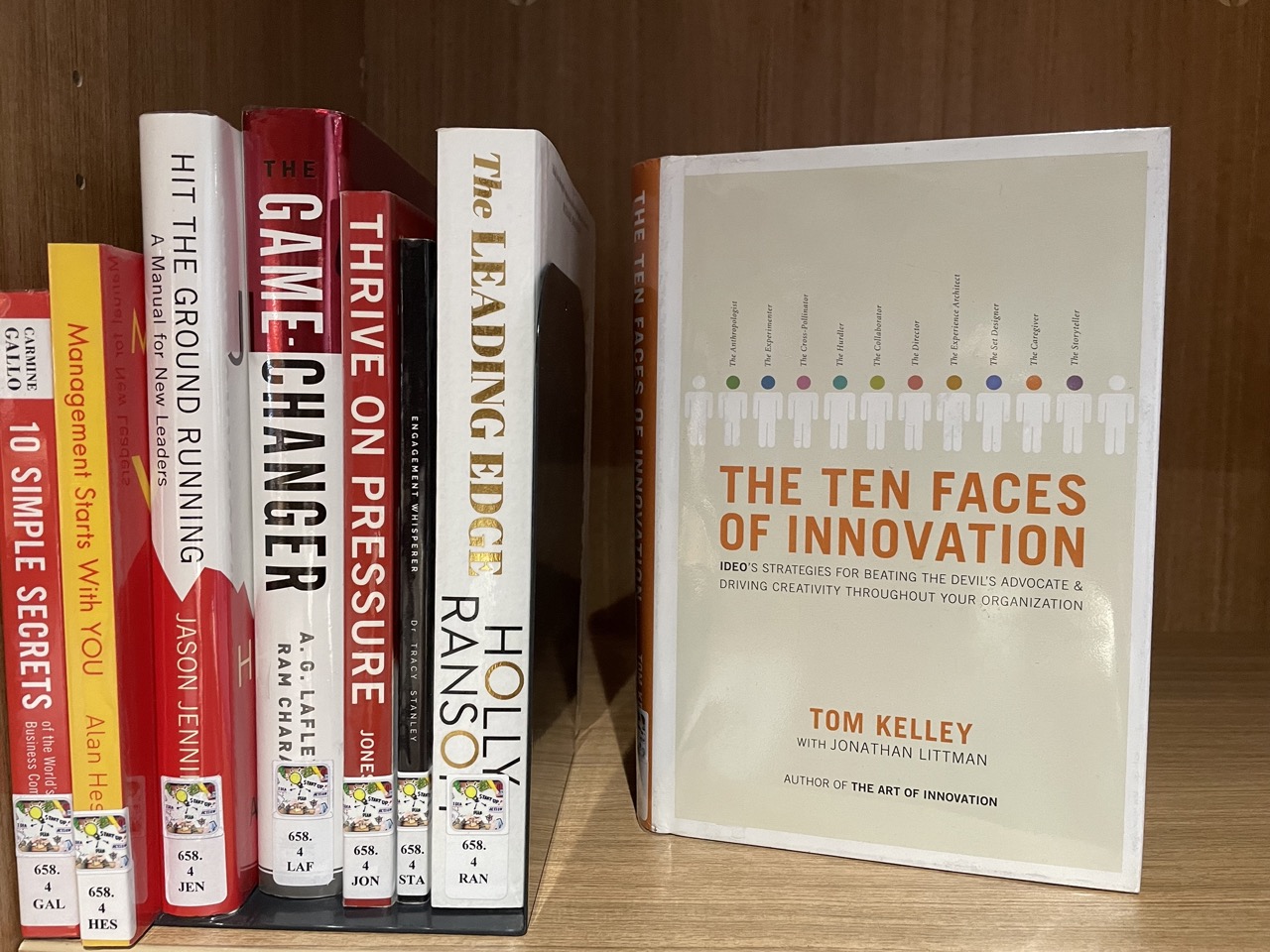

Schools can feel like a busy restaurant sometimes, it’s just that our hungry beast has to be fed at least six times a day. Innovation seems to be the buzz word of the past few years in education. How many Innovation Centres are popping up in schools? I should know, I run an Innovation Precinct. How many new positions have been created with titles like Head of Innovation and Learning? There are school innovation awards, even Innovation Academies.

Innovation and its trendiness certainly isn’t restricted to the education world. It’s a word we see used across sectors. But is innovation more than just the buzz word of the past few years? What exactly is innovation? And what does innovation look like in a school library?

What is innovation?

The definition of innovation is the “process of innovating” or more helpfully, the “introduction of something new”. The definition of innovate is to “make changes in something established, especially by introducing new methods, ideas, or products.” That sounds like my favourite word – change. But what sets innovation apart from change and even creativity is the uniqueness and value of an idea. Innovation is not just change and not just a creative idea or product, it is positive change, something with value (McGrath, 2015). Solving problems is a large part of innovation. Innovation also requires risk taking (Bentley, et al., 2016). Many argue that innovation is not so much a destination as it is a process. A process of exposing new ideas, taking risks and solving problems in a creative and unique way (Marchand & Hanc, 2022). Others argue that it is not a process as much as it is an organisational culture, mind-set, or worldview (Gorzelany, et al, 2021).

Creativity is required for innovation, to look for new ways to approach things. The uniqueness of the idea is what makes innovation different. It’s what sets something apart, instead of just making changes to follow the crowd – which is also necessary and good sometimes. Innovation is making a change that is distinct and unequaled and has value (Bentley, 2016). However, it’s worth noting that sometime determining whether change has value is hard to distinguish without looking backwards. Look at some of the most innovative times or innovative products and now consider them in light of climate change and environmental destruction. Some of the greatest ‘innovations’ have also caused a lot of damage – plastics, for example. And that requires us to continue to innovate to continue to make positive improvements and undo the harm of innovations in the past.

Is it just a buzz word?

The one consistent thing across decades is we are in a time of innovation. Innovation is not new and it is not tied to technology. While technological advancements might be characterised as innovations, an innovation does not need to include technology. Innovation is part of natural behaviour. And it’s not just humans that innovate, animals do as well. There are countless examples of how creative animal behaviour has led to survival and evolution (Deresti Betik & Mostov, 2023).

If innovation is not new or unique, is now really a time of dramatic innovation? The need for innovation as a problem solving method is something we certainly need now, as we have throughout the centuries. Why then are we seeing the word Innovation splashed across the education sector? Perhaps, it’s because education is a sector that, in some ways, looks much the same as decades and centuries ago. Perhaps it’s because our students are facing a world with many challenges and innovation is the only way they are going to be able to problem solve and create positive solutions. If you understand innovation as a process, innovation is a new way to teach students to explore and engage with their world, ideas and problems. If it is a culture and mindset, again, innovation can be used to direct a school or students towards more unique, creative and problem-solving thinking. It moves students away from rote learning and to engaging more in-depth with ideas and concepts. Educators need to think of innovating as actions that significantly challenge key assumptions about schools and the way they operate. Therefore, to innovate is to question the “box” in which we operate and to innovate outside of it as well as within (McGrath, 2015).

What does innovation look like in a school library?

School libraries are not immune to innovation. If you compare the school libraries of today from those from even a decade ago, you’ll see amazing innovation and positive change and new ideas. And I think you could safely say these have great value and have benefited many. School libraries have had to and must continue to innovate to remain relevant and of value to their school communities (Mills-Campbell, 2022).

It’s easy to say we are an innovative school library, a little harder to pin down exactly what that looks like and how to go about it. Further, others argue that to measure for positive change or innovation should not be done within the library alone but within the wider school community (Bentley, et al., 2016). For example, I might say I am innovative by genrefying my collections, creating new wellbeing and entrepreneurship collections, creating new ways to display books and new formats of library lessons, but what’s to say they are unique? These things could be being done – and they are – by librarians around the world. If they are not unique, is it innovation? And what’s to say the changes are positive and have value? I can see immediate positive results – increased borrowing, increased engagement in the library space – but do these extend beyond the library and with the benefit of hindsight, will I have the same thoughts?

Perhaps, though, this should not concern us. Instead we must think creatively about our practice, solve problems and look outside of the box or usual responses to make changes. I like the example of Dorothy Porter. She probably didn’t set out to be innovative, but that’s exactly what she was. When she saw the problems of the Dewey Decimal Classification system, she made changes to ensure it was not as inherently racist, creating a different way to classify books created by African Americans. She solved a problem, was creative, and added great value to the system, to the people using her library, and to generations of library users to come. We don’t innovate for innovation’s sake, we do it to better people’s lives, solve problems and add value.

I come back to the same belief – school libraries must innovate, or at least change and adapt, to improve their library services for their users and to prevent irrelevance.

References

Bentley, E., Pavey, S., Shaper, S., Todd, S., & Webb, C. (2016). The innovative school librarian. Facet Publishing.

Deresti Betik, L., & Mostov, A. (2023). Think like a goat: The wildly smart ways animals communicate, cooperate and innovate. Kids Can Press.

Gorzelany, J., Gorzelany–Dziadkowiec, M., Luty, L., Firlej, K., Gaisch, M., Dudziak, O., & Scott, C. (2021). Finding links between organisation’s culture and innovation. the impact of organisational culture on university innovativeness. PLoS One, 16(10) doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257962

McGrath, K.G. (2015). School libraries & innovation. Knowledge Quest, 43(3), 54–61.

Mills-Campbell, L. (2022). Digital library hub: Innovation during the pandemic. The School Librarian, 70(1), 8-9. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.slq.qld.gov.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/digital-library-hub-innovation-during-pandemic/docview/2640410729/se-2

Leave a Reply